Irini's Orchids

Start with a meadow in May ...

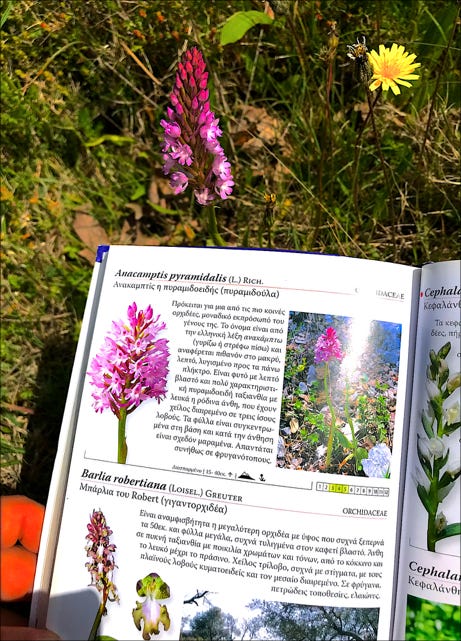

We wanted to find a flower expert to show us the wild orchids of Crete. The rarest orchids grow in hard-to-find enclaves of a particular soil within narrow altitude bands. When you do find them they are smaller than a columbine; some as petite as a lily of the valley. Gazing down on them from hip height they are demure little pips. Kneel to gaze a handspan away and their outer petals of delicate blue, pink, and white part to reveal tiny little tongues whose stamen colours distinguish commoners from rarities — hues that span the saturations from palled to livid to phorescent. Violet tints, mauve hues, shades of scarlet to burgundy, dotted with barely discernible specks of yellow pollen. Imagine Botticelli’s maid emerging from a seashell the size of a pea.

Our web search for orchid experts led us an organisation devoted to matching expert guides and knowledgeable tourists. Most requests are for hikers. Calls for orchid experts are few in a country which promotes its vigorous hiking trails — in part because long-haul walkers are generous in addition to being robust.

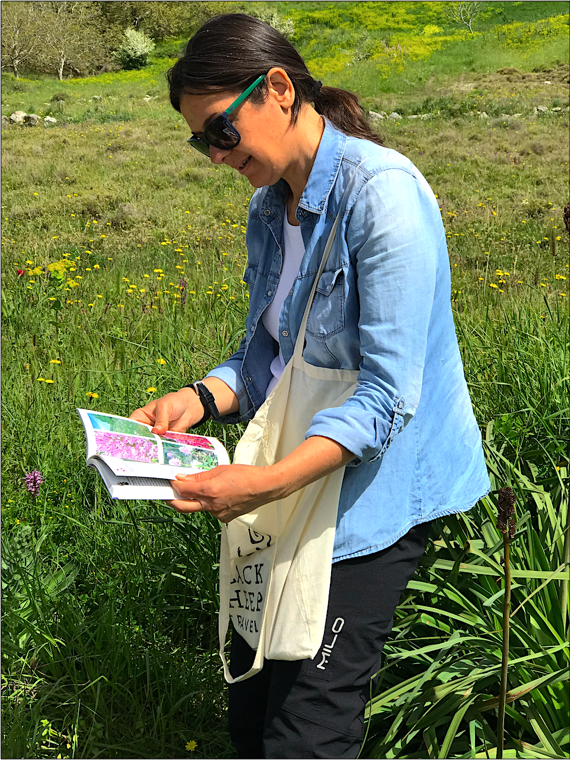

Our guide was named Irini, a tall, slim, raven-haired woman with the long nose, taut high cheeks, slender lips, and smooth complexion in which young Cretan women seem to have a monopoly. Irini felt honoured by us, and we by her. Most of the time Irini is stuck with troupes of outdoorsy types from Scandinavia and Germany who can hike the fetlocks off a mountain goat but whose flower awareness dotes on the big and the yellow. Since Cretans have chased goats up and down those mountains for millennia, Irini can nimbly lead a pack of hikers yet have enough time to do a little wildflower spotting on the side.

Irini knew a high, secluded meadow utterly slathered with flowers. We had never seen so many in so small a place! An Alpine meadow in June is a tepid affair compared with a Cretan meadow in May. We gave up counting after Irini identified thirty-six species in a patch the diameter of a pizza plate. She was in posie heaven. So were we.

Within an hour Irini led us to three rare specimens that took her long minutes to accurately identify using her orchid identification guides. A few were so seldom reported that they weren’t in the botanical apps on her cell phone.

A few were so seldom reported that they weren’t in the botanical apps on her cell phone. Inspecting a plate-sized patch of wildflowers from six inches away reveals treasures you completely miss from two feet away. Kriti rewards a meadow visit with majesties no larger than a thumbnail.

Inspecting a plate-sized patch of wildflowers from six inches away reveals treasures you completely miss from two feet away. Kriti rewards a meadow visit with majesties no larger than a thumbnail.

On the return drive to Rethymnon, Irini stopped an a revered old monasti named Arkadi. It has occupied its site since the fourth century. Legend has it that when St. Paul was shipwrecked on the south coast of Crete he converted a horde of heathen by nonstop talk-talk-talk till everyone gave up in exhaustion and converted just to have some peace and quiet in the community.

Arkadi has a special place in Cretan history. In November 1866 as the Ottoman Turks were about to overrun the village, the entire population squeezed into the refuge of their monastery church. The defenders, led by Konstantinos Giaboudakis, knew the doors would hold for only so long against Turkish battering rams, and what would happen to the women and children once those doors fell. He led a squad of monks to the monastery’s powder room and lit the fuse.

Of the approximately 960 people inside, 864 were killed by the explosion, including all the women and children. As Cretans tell the tale, some 1,500 Ottoman soldiers also died from the blast.

Inside the now-rebuilt church Irini introduced us to the four remaining monks. Beards to their waistlines, faces gullied from a lifetime of tending their flocks both sheep and human, countless hours hoeing their gardens under the blazing Cretan sun, their days are work, prayers, midday meal, prayers, work. They rise at four and sing liturgy till seven. In the evening they sing the liturgy from four till they go to bed at seven.

On the return drive to Rethymnon we discovered that the true orchids in Irini were not those she could reveal to us in the meadows of Kriti, but the orchids in the meadows of her mind.

She began by informing us that we really must make a return visit to the Arkadi Monasti at midnight on Easter Tuesday.

“There is a two-and-a-half hour liturgical service called the Vesper of Holy Tuesday that culminates at midnight to initiate Holy Wednesday, the first day of Orthodox Easter services,” she said.

“Why Tuesday?” I asked.

“On Tuesday at midnight the last song in the liturgy is a twenty-minute solo for tenor called the Troparion. It was written about 850 by an Orthodox abbess from Constantinople named Kassia. She is the first woman known to have composed liturgical music. She was also one of the only two women in the entire Byzantine era to sign her own name to a creative work. The other was Anna Komnemna, who wrote an epic piece about the life of her brother, a great hero of the Byzantine civilization.”

The soft-spoken pride in Irini’s voice was mixed with the shaky voice of someone speaking from the depths of their heart. Her delight in relating a story that was clearly very deep to her brought both of us to full attention. Later we both agreed that Irini at that moment was like watching a magnificent flower bloom.